ASSEMBLING THE ADVOCACY PUZZLE PIECES

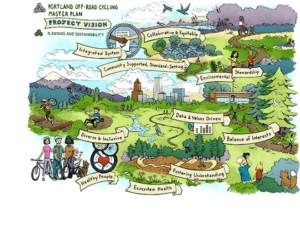

Portland’s Off-Road Cycling Master Plan (ORCMP) — a developing vision for a citywide system of off-road cycling facilities — is helping debunk common misunderstandings that often get in the way of mountain bike access to trails.

Portland’s Off-Road Cycling Master Plan (ORCMP) — a developing vision for a citywide system of off-road cycling facilities — is helping debunk common misunderstandings that often get in the way of mountain bike access to trails.

Because we’re all advocates, I’d like to share a distillation of information that each of you can tap into the next time you’re presented with an opportunity to speak up for our sport. The key points are in bold, in case you’re pressed for time (aren’t we all?).

For those who’d like more detail, dig in to Assessment of Off-Road Cycling Impacts and Benefits from Portland’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, online at https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/584581. All but a few indicated items are from this source.

IMPACTS ON THE ENVIRONMENT

On established trails, mountain biking has no greater negative impact on water and soils than hiking; it’s the design and location of the trail that matters. And the trail guidelines we follow — the IMBA (International Mountain Bicycling Association) books Trail Solutions and Managing Mountain Biking — are widely respected outside the mountain biking community.

On established trails, mountain biking has no greater negative impact on water and soils than hiking; it’s the design and location of the trail that matters. And the trail guidelines we follow — the IMBA (International Mountain Bicycling Association) books Trail Solutions and Managing Mountain Biking — are widely respected outside the mountain biking community.

Mountain biking has no greater potential than hiking to negatively impact vegetation on established trails. However, rogue mountain bike trails have become a primary argument for limiting access. Loss of vegetation precipitates soil erosion, negatively impacting water systems. Of course, trail construction brings the greatest impact, but significantly increasing trail traffic has little additional effect on vegetation.

The impact of mountain biking on wildlife activity is species-dependent, in some cases more, in others the same or less, than hiking. Wildlife disturbance extends further into the landscape than other impacts, which tend to be limited to the trail corridor. A key consideration is that the trail, regardless of the activity it supports, fragments habitat, negatively impacting species health and diversity.

IMPACTS ON SAFETY AND HEALTH

Hiker concern over personal safety on trails shared with mountain bikers is a significant perceptual issue, one not born out by actual incident data. Consider that roughly only one in 10 hikers are mountain bikers, and this lack of familiarity with our sport engenders a view that mountain bikers are riding too fast for the conditions. The resulting fear pervades the hikers’ experience and does not diminish over time (despite, in one study, a three-fold increase in mountain bike use over two years with minimal actual safety issues). Education, signage, volunteer trail patrols, and trail design are more effective in reducing this perceived user conflict than trail access regulation, such as limiting bikes to double-track lanes.

Hiker concern over personal safety on trails shared with mountain bikers is a significant perceptual issue, one not born out by actual incident data. Consider that roughly only one in 10 hikers are mountain bikers, and this lack of familiarity with our sport engenders a view that mountain bikers are riding too fast for the conditions. The resulting fear pervades the hikers’ experience and does not diminish over time (despite, in one study, a three-fold increase in mountain bike use over two years with minimal actual safety issues). Education, signage, volunteer trail patrols, and trail design are more effective in reducing this perceived user conflict than trail access regulation, such as limiting bikes to double-track lanes.

Switching over to health, keep in mind that cycling is the second most popular outdoor activity among youth (whose bikes are typically dirt-oriented), and fourth among adults 25 and over. Across all ages, mountain biking participation has increased 2.8% in the last three years, while road cycling has diminished 0.8%.(1)

While it’s well understood that outdoor recreation improves health and well-being, did you know it also improves academic performance and self-esteem?(2,3)

Coming back to youth, half of all Americans see childhood obesity as serious enough to warrant immediate investment(4) and most obese 10- to 13-year-olds become obese adults.(5) On the other hand, children who ride two or more times a week are less likely to be overweight(6) and can inspire their siblings and parents to start riding.

IMPACTS ON ECONOMIC ACTIVITY

The Portland metro area is the hub of Oregon’s cycling industry, holding three quarters of Oregon’s bicycle-related manufacturing jobs, and nearly half of its sales jobs. The number of bicycle-related businesses in Portland has increased ten fold since 2002. The off-road component of the Portland’s cycling industry total economic contribution is in the range of $60 million annually, including wages and salaries, property income, and business tax revenue. Off-road cyclists constitute slightly more than half of all Oregon cyclists.

The Portland metro area is the hub of Oregon’s cycling industry, holding three quarters of Oregon’s bicycle-related manufacturing jobs, and nearly half of its sales jobs. The number of bicycle-related businesses in Portland has increased ten fold since 2002. The off-road component of the Portland’s cycling industry total economic contribution is in the range of $60 million annually, including wages and salaries, property income, and business tax revenue. Off-road cyclists constitute slightly more than half of all Oregon cyclists.

Three quarters of Portland’s bicycle-related businesses cited off-road cycling facilities as important to the growth of this local industry, and nearly all stated Portland does not have that now.

Beyond supporting industry growth, off-road cycling facilities can be more cost-effective than traditional preventive strategies in reducing new cases of many chronic diseases.(7) As one example of this, Portland recently estimated that The Intertwine trail network saves the city approximately $115 million per year in healthcare costs.(8)

Above this, there’s tourism. Nearly 90,000 Multnomah County residents are off-road cyclists, spending over $16 million annually on cycling trips. And trail building can be profitable: trails in Teton County, Wyoming create an annual economic benefit of more than $18 million, yet, over a decade, their total cost was one tenth of their annual benefit.(9)

SUMMARY

One of the most popular outdoor activities, mountain biking holds significant potential to improve physical and mental heath, academic performance, self esteem, and the sense of well being, all the while generating significant economic benefit.

Generally speaking, mountain biking is no more damaging than hiking. Trail location, design, construction, and maintenance have a far greater potential impact on the environment than trail activity, and reputable trail builders like the Northwest Trail Alliance follow practices that are widely respected and adopted.

Two issues stand out as impeding trail access: the building of rogue trails and the perception of user conflict. Beyond advocacy, our individual behavior — staying on sanctioned trails and respecting our fellow trail travelers — becomes key to trail access.

I’ll close with a quote from Pinkbike’s Vernon Felton: “It’s time we all stepped out of the dark and helped other people see the light.”

REFERENCES

1. The Outdoor Foundation, Outdoor Recreation Participation Topline Report 2016, available online at http://www.outdoorfoundation.org/pdf/ResearchParticipation2016Topline.pdf

2. Singh, A., et al., 2012, Physical activity and performance at school: A systematic review of the literature including a methodological quality assessment, Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine

3. Fox and Corbin, 1999, Green Exercise: Complementary Roles of Nature, Exercise and Diet in Physical and Emotional Well-Being and Implications for Public Health Policy, CES Occasional Paper 2003-1, University of Essex

4. Quinlan, A., et al. in Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2010, F as in Fat: 2010: How Obesity Threatens American’s Future

5. Whitaker, R., et al., 1997, Diet, Physical Activity, and Sedentary Behaviors as Risk Factors for Overweight in Adolescence, Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine

6. Dudas, R., and M. Crocetti, 2008, Association of Bicycling and Childhood Overweight Status, Ambulatory Pediatrics

7. Roux et al., 2008, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Cost Effectiveness of Community-Based Physical Activity Interventions, American Journal of Preventive Medicine

8. Beil, K., 2011, Physical Activity and the Intertwine: A Public Health Method of Reducing Obesity and Healthcare Costs

9. Kaliszewski, N., 2011, Jackson Hole Trails Project Economic Impact Study, University of Wyoming